Noble | Presidents Letters

newpres40

Fly-In Club's President's Letter

by Chris Pilliod

40th President's letter by Chris Pilliod

This is my 40th President's letter. The number 40 has always had a special place in my heart. It was a signature number for my father, who soon turns 92 and is doing well in Swanton, Ohio, the town he was born in back in 1919. One of his first jobs as a kid in 1932 was a caddie at the local golf course Valleywood, west of Toledo-at the time the only course in the county. This was well before any carts and caddies, the boys carrying the clubs for the old geezers, was a way of life on the golf courses-heck, for that matter golf carts were rare and only for the wealthy when I started playing in 1965.

Regardless, the caddies had a badge they wore, I guess since old guys could remember numbers better than names. My father wore caddie badge #40, and for 5 hours he would slog around the course carrying a set of clubs for 25 cents during the Depression. He liked caddying doubles (two bags) when he could make a whopping 50 cents! Interestingly, the golf course he grew up caddying on would be the same course I played endlessly as a youngster growing up and through college. He joined after he got out of WWII in 1947 and at 91 years old is now the oldest and longest member of the club. I often ask him what changes were made to the course over the years as I would like to know how it played back in the 30's. Surprisingly very few, and to be truthful, almost no changes had been done. One par-3 was converted to a par-3 along US Highway-2, and back in the woods a par-5 was converted to a par-4. Some earth was moved here and there but the way I played it in the 60's and 70's was how it was basically built in 1929.

And when I say I played it endlessly, I wasn't just whistlin' Dixie. Just about everyday it was "Hi, Mom, Bye Mom". I would rush through my bowl of cereal, sling my golf bag over my shoulders, hop on my Schwinn Typhoon and peddle two miles to Valleywood Golf Course. Sometimes my brother would join in and occasionally a few friends as well. Often I would cut along the railroad tracks that connected Toledo with Chicago and use it as a fun shortcut. But one day we got attacked by some migrant workers aimlessly walking along the tracks and it put the fear of God in us so we never went that way again.

But I was the most serious of all, and loved to play every day, regardless of weather. Just the other day here in Pennsylvania my two oldest boys played a 27-hole tournament in some warm weather and after carrying their clubs all day they were anxious to slump in the car and on the way home they complained of their enormous fatigue. I related to them how I recalled one especially hot summer day, how I played 54 holes carrying my clubs basically from sunrise to sunset. If you ever want a real workout, try doing this for yourself-- I am sure I physically could never do that again.

One warm sunny day in 1969 or '70 a group of six of us kids from the neighborhood met at the course. There was a giant Oak tree next to the Maintenance building that acted as a meeting point where we would park our bikes and walk to the 10th tee nearby. Usually that early in the morning it was hard getting off on the crowded 1st tee, but none of the golfers had made the turn yet so we would always begin play on the backside, which was wide open.

The chances of what happened next are about one in a million, unless you're young kids that never earned a penny in your life and didn't know what being organized and well-prepared meant. I reached in my bag and grabbed a tee but much to my surprise after digging around for several minutes I announced, "I don't have any golfballs!!!" And then one after another of us came to the same grim realization-none of us had a single golfball as the night before we had a makeshift golf course set up in our large backyard and never picked up from our carryin' on late into the night.

One of the older kids looked around and eyeing me asked, "OK, now who's gonna peddle back home and get us all some golfballs???" Quick thinking, that's when I responded, "Why don't we just go down to the creek and find some???" Swan Creek ran right through the middle of the course and confounded those players who would slice a drive #11 and #18 and would catch a fat shot on #8 and #17. It was a warm day and we all had shorts on so within a few minutes our socks and tennis shoes (we couldn't afford spikes yet) and shirts were off and before you knew it six young kids were sprinting down the middle of the course heading for the creek. I can only imagine what those stodgy members sitting in the restaurant enjoying breakfast or the old geezers teeing off on the first hole were thinking when they laid eyes on this gaggle of kids flying towards the creek. It only gets better… we wasted no time wading in the creek and within 10 or 15 minutes found more than enough balls to get us through the day. But someone slipped on a rock in the creekbed and fell in. As he flailed around trying to compose himself another kid just dove in headfirst and before you knew it all of us were frolicking around like it was the swimming pool Valleywood never had. I don't remember our golf scores from that round or anything else about the entire day, I just remember swimming in Swan Creek early n the morning and golfing with wet shorts all day-it's great to be a kid.

That Swan creek is also very prone to flooding, and when the waters swelled over the banks the course would close for weeks at a time. And with the waters came the huge carp. So us kids would grab our frog spears and start wading the fairways along the creek looking for these great big old carp to flop around. Our little frog spears were no match for a 20-pound carp but we had fun chasing them.

My boys have never golfed at Valleywood and often ask about my days as a kid learning the game there. My patent response is, "I used to know every blade of grass on the place, but if I ever go back they're gonna have to remind me of their names." So I have dedicated myself this summer while on our vacation back home we take off an afternoon and tee it up at ole place.

OK, on to coins… I'd like to start out by saying next time you see Rick Snow or a staff member at Heritage Auctions, please, please thank them for the continued support they are showing the club. Without Heritage's offering to print the Ledger at no charge the club would be tapping into our precious cash reserves. So please make an effort to send along your thanks.

Numismatically, in studying Indian Cents one thing that has puzzled me and other observers is the lack of mintages for the years 1866 through 1878. In 1982, when a cent was worth far less, the United States produced 18 billion (yes, billion) circulating cents, or roughly 72 issues per American alive. 1877 marked the ebb tide of small cent production with just 852,000 struck. With a national population of 45 million, this represents just 0.02 cents coined per American, or an simpler way of viewing it, 53 Americans for every cent produced in 1877. So why such a discrepancy???

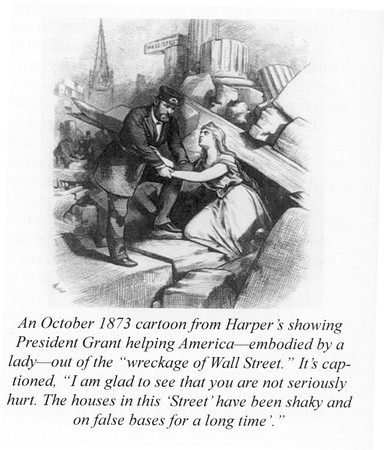

A number of reasons exist, and three come to mind quickly. For this letter we'll explore what was going on in the nation during the 1870's. Just as the early 1930's saw a sharp decline in coinage production as a result of the Great Depression and resultant lack of demand for commerce, many of us are likely unaware of the severe economic blight facing the States beginning in 1873. The Depression of 1873, or the "Long Depression" is rivaled only by the Great Depression in severity. The Depression impacted demand for coinage, and while it does not explain the light mintages of 1866 through 1873, it does help assign a cause for the coinages and legislation of 1873 and the years immediately thereafter.

The Long Depression was a worldwide economic crisis, felt most heavily in Europe and here in the United States, which had been experiencing strong economic growth fueled by the Second Industrial Revolution and the conclusion of the Civil War. At the time, the episode was labeled the Great Depression, and held that title until the Great Depression of the 1930s I just mentioned. Though a period of general deflation and low growth began in 1873 and lasting until about 1896, it did not have the severe economic and spectacular breakdown of the 1930's Great Depression. Because of the large increases in U.S. industrial production, GNP and real product per capita, historians have questioned whether there was really a U.S. depression in anything other than profits.

It was most notable in Western Europe and North America, at least in part because reliable data from the period is most readily available in those parts of the world. The United Kingdom is often considered to have been the hardest hit; during this period it lost some of its large industrial lead over the economies of Continental Europe and especially to America.

In the United States, economists typically refer to the Long Depression as the Depression of 1873-79, kicked off by the Panic of 1873, and followed by the Depression of 1893, book-ending the entire period of the wider Long Depression. The National Bureau of Economic Research dates the contraction following the panic as lasting from October 1873 to March 1879. At 65 months, it is the longest-lasting contraction identified by the NBER, eclipsing the Great Depression's 43 months of contraction. After the panic, the economy entered a period of rapid growth, with the U.S. growing at the fastest rates ever in its history in the late 1870s and 1880s. This can be seen in the rapid rise in cent mintages beginning in 1878 and through 1889 with a slight dip in the mid-1880's. Using the coinages of silver as a bellwether for the economy during this period can be misleading because Bland-Allison Act virtually monopolized all the metal into the production of Silver Dollars.

The period preceding the depression was dominated by several major military conflicts and a period of economic expansion. New technologies in industry such as the Bessemer converter for greatly increasing steel production were being rapidly employed and the era of the railroads were booming. The end of the Civil War led to a brief post-war recession (1865-1867) but gave way to an investment boom, focused especially on railroads on public lands in the West - an expansion funded greatly by foreign investors.

Run on the Fourth National Bank,

No. 20 Nassau Street,

New York City, 1873.

From Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper,

And then there was 1873. The Panic of 1873 has been described as "the first truly international crisis." The optimism that had been driving booming stock prices in central Europe had reached a fever pitch, and fears of a bubble culminated in a panic in Vienna beginning in April 1873. The collapse of the Vienna Stock Exchange began on May 8, 1873 and continued until May 10, when the exchange was closed; when it was reopened three days later, the panic seemed to have faded, and appeared confined to Austria-Hungary. Financial panic arrived in America only months later on Black Thursday, September 18, 1873 after the failure of the banking house of Jay Cooke and Company over the Northern Pacific Railway. The Northern Pacific railway had been given 40 million acres (160,000 km2) of public land in the West and Jay Cooke sought $100,000,000 in capital for the company; the bank failed when the bond issue failed, and was shortly followed by several other major banks. The New York Stock Exchange closed for ten days beginning on September 20.

The primary cause of the price depression in the United States was the tight monetary policy that the U.S. followed to get back to the gold standard after the Civil War. The U.S. was taking money out of circulation to achieve this goal; therefore, there was less available money to facilitate trade. Because of the monetary policy described above the price of silver started to fall causing considerable losses of asset values. However, by most accounts, after 1879 production was growing, thus further putting downward pressure on prices due to increased industrial productivity, trade and competition.

The speculative nature of financing due to both was paper currency issued to pay for the US Civil War and rampant fraud in the building of the Union Pacific Railway up to 1869 culminated in the panic. Railway overbuilding and weak markets collapsed the bubble in 1873. Both the Union Pacific and the Northern Pacific lines were center in the collapse.

Because of the Panic of 1873, governments depegged their currencies to save money. The demonetization of silver by European and North American governments in the early 1870s was certainly a contributing factor. The Coinage Act of 1873 in America was met with great opposition by farmers and miners, as silver was seen as more of a monetary benefit to rural areas than to banks in big cities. In addition, there were Americans who advocated the continuance of government-issued fiat money (United States Notes) to avoid deflation and promote exports. The western US states were outraged-Nevada, Colorado, and Idaho were huge silver producers with productive mines, and for a few years mining abated. The resumption of the US government buying silver was enacted in 1890 with the Sherman Silver Purchase Act.

Monetarists believe that the 1873 depression was caused by shortages of gold that undermined the gold standard, and that the 1848 California Gold Rush and the 1898-99 Klondike Gold Rush helped alleviate such crises.

In the United States, the Long Depression began with the Panic of 1873. The National Bureau of Economic Research dates the contraction following the panic as lasting from October 1873 to March 1879. At 65 months, it is the longest-lasting contraction identified by the NBER, eclipsing the Great Depression's 43 months of contraction. Following the end of the episode in 1879, the U.S. economy would remain unstable, experiencing recessions for 114 of the 253 months until January 1901.

In the United States, nominal wages declined by 25% during the 1870s, and as much as 50% in some places, including here in Pennsylvania. The collapse of cotton prices devastated the already war-ravaged economy of the South and although farm prices fell dramatically, American agriculture continued to expand production.

Thousands of American businesses failed, defaulting on more than a billion dollars of debt. One in four laborers in New York were out of work in the winter of 1873 and nationally a million became unemployed.

The sectors which experienced the most severe declines were manufacturing, construction, and railroads. The railroads had enjoyed the status as a tremendous engine of growth in the years before the crisis, yielding a 50% increase in railroad mileage from 1867 to 1873. After absorbing as much as 20% of US capital investment in the years preceding the crash, this expansion came to a dramatic end in 1873; between 1873 and 1878, the total amount of railroad mileage in the United States barely increased at all. Recovery began in 1878. The mileage of railroad track laid down increased from 2,665 miles in 1878 to 11,568 in 1882. Construction began recovery by 1879; the value of building permits increased two and a half times between 1878 and 1883, and unemployment fell to 2.5% in spite of high immigration. Compare this to 10% unemployment of 2011!!!

The recovery, however, proved short-lived. Business profits declined steeply between 1882 and 1884. The economic decline became another financial crisis in 1884, when multiple New York banks collapsed; simultaneously, in 1883-1884, tens of millions of dollars of foreign-owned American securities were sold out of fears that the United States was preparing to abandon the gold standard. This financial panic destroyed eleven New York banks, more than a hundred state banks, and led to defaults on at least $32 million worth of debt. Unemployment, which had stood at 2.5% between recessions, surged to 7.5% in 1884-1885, and 13% in the northeastern United States, even as immigration plunged in response to deteriorating labor markets. This can be seen in the dip in cent production of 1884 through 1886.

But by 1887 the economy had recovered and except for a short recession of 1893-1894 growth continued robustly through the early 1900's. And not surprisingly demand for coinage followed suit.

In the next issue we will discuss what led to the very low coinage production of the late 1860's and early 1870's.

NOTE: Credit to Wikipedia and other sources for some of this information.